It All Comes Out In The (Green)Wash

To paraphrase Gordon Gekko, ‘green is good’. But only when it’s done sustainably. Faced with ever-tightening timing and budgetary pressures, the quest for true ‘green development’ continues to be an ongoing conundrum for many of the world’s developers, architects and urban designers.

The concept of ‘greenwashing’ first came to prominence in the 1980s. Largely a marketing-driven phenomenon, it was born from the desire for businesses to enjoy the benefits of being ‘seen’ to be environmentally conscious, even when commercial practicalities (be they financial, attitudinal or even technological) prohibited it from actually being achieved.

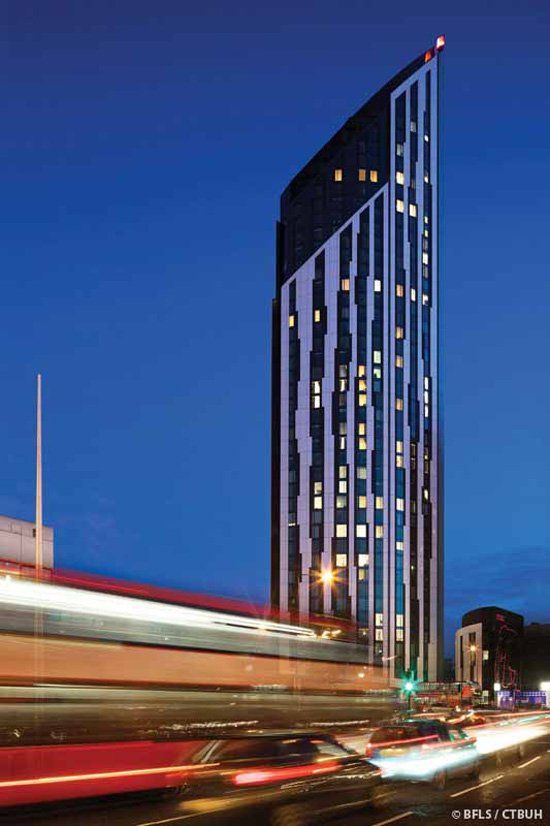

Virtually no industry has been immune, with examples of greenwashing everywhere from tourism, transport and technology to fashion, food and finance. One of the more infamous cases from our own industry can be found standing 148-metres high above the streets of south London.

All wind and hot air.

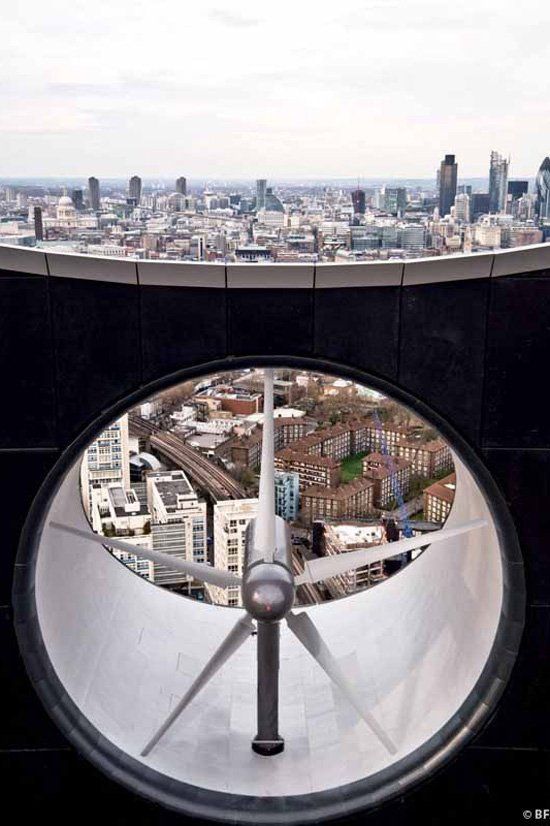

When completed in 2010, the design of the 43-storey ‘Strata’ residential tower at Elephant & Castle set tongues wagging with its triumvirate of commanding 9-metre integrated wind turbines accompanied by all manner of environmental promises and fanfare.

While it was initially claimed the turbines would harness the wind to produce almost 10% of the tower’s entire annual electricity needs, they’ve never been used. In fact, nearly a decade on the turbines still sit motionless and have been described by The Architectural Review as, “an eco-bling tiara on an edifice of hubris”. At one point there were even reports of installing conventionally-powered motors to make them turn and deflect unwanted attention. Rubbing further salt into the eco-wounds, the development was awarded the dubious honour of Worst Building of the Year in the 2010 Carbuncle Cup, “for services to greenwash, urban impropriety and sheer breakfast-extracting ugliness”.

Theory meets reality.

Clearly not all instances of greenwashing are as extravagant. The increasing popularity of green façades here in Australia is something we’ve been keeping a very keen eye on ourselves in recent years. Green-inspired features such as plant curtains, living walls and vertical forests are all fantastic in theory. But unless they’re truly integrated into the wider planning scheme for public and community spaces, many are destined to die a slow death at the hands of costly and labour-intensive maintenance schedules – especially if massive amounts of energy and water are required to keep them alive, year after year. Then there’s also the question of ‘embodied carbon’ to be considered, the upfront carbon emissions incurred to construct these features in the first place, which may far outweigh any potential environmental benefits.

As leading French landscape architect, Céline Baumann, told the industry magazine Dezeen in October 2019, plants will continue to be used to greenwash developments until landscape architecture is given a far bigger role in urban planning. “Greenery is unfortunately too often used as an alibi for new developments, by wrapping buildings in green as sole legitimisation of an otherwise unsustainable project,” Baumann said. “Green surfaces such as walls and roofs are often very high maintenance and demand a lot of water and chemicals to thrive.”

It’s a critical point Baumann makes. For while such features provide a wonderful selling point for a new property trying to attract buyers or tenants in a competitive market, what happens in 2, 3 or 5 years’ time? Self-sufficiency is the key and that can only be truly achieved through a more considered, collaborative and integrated approach to soft and hard landscaping that begins right at the beginning of projects – in the planning stages.

The good news is, this presents a wonderful opportunity for landscape architects to come to the fore with new ideas and approaches. “Landscape architects today can be radical if they are given a bigger role in city planning and new developments,” suggests Céline Baumann. “Their understanding of open spaces as well as of natural processes is crucial to allow the creation of more inclusive, liveable, and truly sustainable cities.” We wholeheartedly agree!

A greener future?

Australia’s appetite for more sustainable urban development has never been greater. But there’s still a fine line between commercial necessities and environmental niceties, something that will likely continue for some time yet. In the case of many projects it’s simply unrealistic to expect fundamental change overnight. But as we all strive to improve the environmental footprints of everything we design, build and maintain, we all have a role in helping to put an end to the concept of greenwashing, once and for all. If the intention is to label a project ‘green’, let’s take a stand to make sure it really is. For the benefit of today, but also tomorrow.

More from Fleetwood Files.

Explore

Certifications

Environmental Management : ISO14001

Quality Management : ISO 9001

OHS Management : ISO 45001

All Rights Reserved | Fleetwood Urban | Privacy Policy